The Maestro of Chagrin Falls

Friday | April 26, 2013 open printable version

open printable version

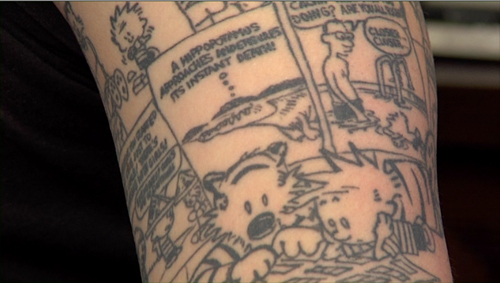

A fan’s tattoo, from Dear Mr. Watterson (2013).

DB here:

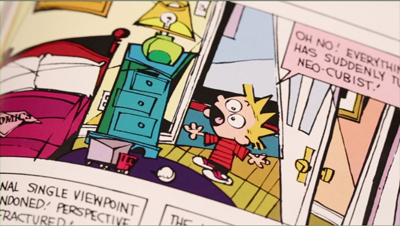

Bill Watterson, creator of Calvin and Hobbes, was probably the best cartoon draftsman since Carl Barks and Walt Kelly. His versatile line could be thick or thin, fluent or jagged. His coloring was rich, his layout experimental in the Herriman vein. His energetic picture stories provided zany humor and an unsentimental look at childhood imagination.

If Schulz treated kids as miniature adults, complete with obsessions and neuroses, Watterson saw Calvin as an adolescent in a child’s body, a rebellious teenager-to-be surrounded by adversaries and fools. Schulz’s Peanuts kids suffer in thin, wriggly lines, but Calvin’s mood swings from rage to rapture are rendered by manic exaggeration in the classic cartoon tradition. Meanwhile Hobbes, contrary to his name, exercises a gentling effect, becoming a tolerant Superego to Calvin’s Id.

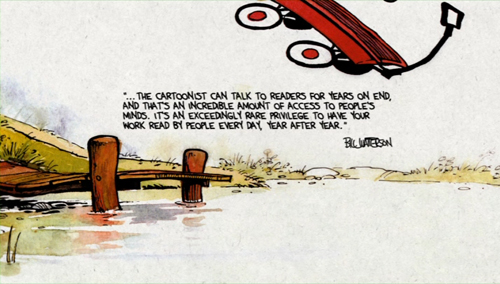

Watterson was the Pynchon of cartoondom. His studio in Chagrin Falls, Ohio yielded a solitude rare for a publishing celebrity. He almost never appeared in public and seldom answered mail. In one of his rare public gestures, he criticized syndicate power, the tired old strips put on life support, and the scramble for licensing deals. Accordingly, he permitted no merchandising beyond book collections. Any Calvin and Hobbes toys or T-shirts or decals you see around you are DIY handicraft. After ten years Watterson simply halted the strip, an abnegation that drove his millions of admirers to despair. And he has remained reclusive.

Dear Mr. Watterson, which won a Golden Badger award at our Wisconsin Film Festival, sprang from Joel Schroeder’s fondness for the strip. He realized early on that interviewing Watterson wasn’t in the cards. So he set out to find ordinary readers who would testify to their love for Watterson’s creation. He found plenty of eloquent ones, but the movie is no mere fanboy indulgence. Schroeder’s travels took him to many of today’s top cartoonists, from Berkeley Breathed to Stephan Pastis, as well as critics and syndicate executives.

By outlining the shape of Watterson’s achievement in comics history, Dear Mr. Watterson mutes its admiration with regret, and not merely because Watterson quit at the height of his popularity. The film shows that, as one interviewee puts it, Calvin and Hobbes is very likely the last great comic strip.

Why? The conditions of publishing have a lot to do with it. As newspapers got thinner and smaller, the space allotted to comics shrank. Complex compositions and spacious storytelling became difficult in the slots allotted to Sunday strips, while the daily panel formats were minuscule. Only the sketchiest drawing survives the reduction.

The squeeze was starting in Schulz’s day: Peanuts was the beginning of the “minimalist” look of Cathy and Fox Trot. Watterson’s bold drawing style and appetite for scale posed problems for publishing. Ironically, as Schroeder pointed out in his Q & A, the sort of freedom and flexibility Watterson sought would become available a decade later on the Net.

Something else suffocated comics creativity. Just as tentpole films need an array of ancillaries, a successful cartoon demands the womb-to-tomb merchandising that Watterson foreswore. Children need to be hooked on the franchise before they can read. Garfield clothes and toys introduce infants to a pudgy beast that will stalk them throughout their lives, on lunchboxes and calendars and mugs and mousepads and refrigerator magnets and TV shows and “Is it Friday Yet?” placards for office cubicles. Watterson realized, I think, that being surrounded forever by leering images of cute creatures was one version of Hell.

Schroeder, a graduate of UW—Madison, has made a smart, touching movie. It deserves wide circulation and even, I should say, a PBS airing. It’s at once a tribute to a fine artist, a probe into comics history, and a revelation of how integrity can be maintained in the era of Monetization. Turning down hundreds of millions of dollars, Watterson in effect said something that almost no one imagines possible today: I don’t need that much money.

One observer comments that when Calvin and Hobbes ceased, many critics expected its fan base to dwindle, because it wouldn’t be maintained by all the spinoffs. Instead, parents pass down their Watterson paperbacks as family heirlooms. Fans have the lavish three-volume compendium of the strips, which is selling briskly on Amazon, while school libraries are replenishing their holdings of the slim anthologies. Our children are following the adventures of the hyperkinetic brat and his imaginary tiger in the best way: By reading books.

P.S. 2 May: Chris Blunk of Through a Glass Productions writes this followup:

Coincidentally, this past Sunday I met John Glynn, who works at Andrews/McMeel promoting their properties to Hollywood (such as Garfield and Over the Hedge). He was at the Free State Film Festival in Lawrence, Kansas where he showed the Sundance-boosted Small Apartments, also based on an Andrews/McMeel property. He was the first person I’d ever met who has any kind of semi-regular contact with Watterson. Though Watterson retains nearly all ancillary rights to his characters, A/M-Universal consults him on book printings, electronic distribution, etc.

While there were several tidbits that thrilled a fan like me, one item he mentioned particularly pertained to your article. He claimed that traffic at the Universal comics website (www.gocomics.com) is by and large driven by the Calvin and Hobbes classic – i.e. rerun – strips. The majority of visitors to all other comics on the site – including popular current strips like Get Fuzzy, Pearls Before Swine, Dilbert, etc, – arrive through Calvin and Hobbes.

So in addition to being propagated through handed-down book collections, as you pointed out, Calvin has managed to attract new fans and dominate comics circulation even in the new frontier of the web that grew into being long after Watterson’s retirement. And this with no new strips published in the past 20 years.

He told a couple other anecdotes that were similarly surprising. Such as a time in the early 90s when Spielberg was involved in some animation projects (Tiny Toon Adventures, Family Dog, Animaniacs, etc) and made inquiries about the rights to Calvin and Hobbes. According to Glynn, Watterson turned down a direct phone call with Spielberg himself reasoning they had nothing to discuss.

Thanks to Chris for his thoughts and information, and for reading our blog.

P.P.S. 16 July 2013: Gravitas Ventures announces that it will be releasing Dear Mr. Watterson on theatrical and VOD in November.

Dear Mr. Watterson.